Once upon a time, there was a phone company—or rather, the phone company. AT&T Corp., the venerable "Ma Bell," provided nearly all telephone service to nearly all Americans for decades... until it didn't. The company infamously broke up on New Year's Day in 1984, splitting into the seven "Baby Bells," regional carriers that could compete with other long-distance providers for consumer dollars.

The split wasn't just for funsies. The baby Bells were the ultimate result of a settlement between AT&T and the Justice Department, the culmination of an antitrust case that began nearly a decade earlier. It was the first time the feds broke up a communications company for antitrust reasons—and 35 years later, it retains the dubious distinction of being the last.

The decades of deregulation since the Reagan administration have brought us to a whole new era of massive corporate consolidation and the rise of a new wave of conglomerates in sectors that didn't even exist 40 years ago. The growth at the top in tech has been particularly stratospheric: Amazon, Apple, Facebook, Google, and a handful of others that have risen since the turn of the century now dominate our economy and our communications in a powerful way.

Critics from all sides, however, now consider today's tech titans to be too powerful, and all four companies have in recent years faced several investigations probing a central issue: antitrust law. Dozens of probes are going on right now under the auspices of dozens of state, federal, and international bodies using dozens of state, federal, and international statutes. What all of these antitrust laws have in common at their core, though, is the concept of playing fair—especially when it comes to the biggest player in the room.

Antitrust 101: More than monopolies

The newest antitrust law on the books in the United States dates to the 1970s; the oldest comes from more than a century ago, passed in response to the behavior of the railroad, steel, and oil magnates of the first Gilded Age.

The Sherman Act of 1890 was short and sweet, as far as laws go. It declared contracts, corporate trusts, or conspiracies "in the restraint of trade or commerce" between states or nations to be illegal. The Act also outlawed monopolies: "Every person who shall monopolize, or attempt to monopolize, or combine or conspire with any other person or persons, to monopolize any part of the trade or commerce among the several States, or with foreign nations, shall be deemed guilty of a felony."

Most of the juicy stuff in modern antitrust, however, comes from the 20th century. The Federal Trade Commission Act of 1914 established the FTC, with the explicit mandate not only to protect consumers from "unfair or deceptive" acts, but also to "prevent unfair methods of competition" that affect commerce. Those "unfair methods" were outlined in a companion piece of law: the Clayton Antitrust Act, also signed into law in 1914, which significantly refined and strengthened the Sherman Act.

The Clayton Act expanded the scope of antitrust law to deal not just with monopolies, but specifically with anticompetitive behavior—basically, tactics that unfairly boost a company into a dominant market position or that unfairly keep a dominant company at the top and suppress competitors. At the highest level, these behaviors basically fall into two big buckets.

The first is growth through acquisition: you can't just buy out your primary competitor if the field isn't big enough for other companies to pose real competition. Consider the mobile market, for example: regulators decided the imminent union of Sprint and T-Mobile isn't anticompetitive, because T-Mobile and Sprint are the two smallest of the four major players. Even with one of them taken out, the market still has three national carriers. (And under the agreement with regulators, there will theoretically be a fourth carrier again. Someday.)

But if AT&T and Verizon, the two dominant US mobile carriers by far, ever tried to merge operators, even the current crop of business-friendly regulators would almost certainly bring that proposal to a screeching halt. A deal of that magnitude would create a company so far beyond the reach of any potential competitor that no current player or new business could ever reasonably be expected to stand a chance of catching up.

The second metaphorical bucket holds the whole category of dominance through unfair dealings, which can be done by one company or as an agreement among several. One kind of unlawful anticompetitive behavior you find here is classic price-fixing. Recently, for example, StarKist was ordered to pay a $100 million fine after it and Bumble Bee were both found guilty of conspiring to fix prices in the canned tuna market, which is largely controlled by three companies.

Unfair behavior can also include a whole array of tactics undertaken by a single company, such as price discrimination, predatory pricing, or certain kinds of exclusivity requirements. These are the kinds of behaviors a federal judge found Qualcomm guilty of back in May, when she ruled that the company's business practices "strangled competition" with exclusive deals and patent licensing fees that charged device makers even when their products used a different brand of chip.

In modern analyses, regulators are concerned not necessarily with competition for its own sake, but rather with the negative effects that follow when competition disappears. A market with little-to-no competition tends to see prices go up while the quality of the product and service degrade, affecting not only individual consumers but also suppliers and commercial buyers at every level. A player with an extreme dominant market position can leverage its dominance on suppliers that can affect competition several links up or down the chain.

So who's investigating whom?

Concerns about big tech's anticompetitive behavior have occasionally bubbled up for decades. But building pressure seems to have exploded coming into this year, and most major developments in the US seem to have hit just within the past six months:

- March 8: Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) announces a proposal to break up Amazon, Facebook, and Google as one of the policy planks of her 2020 presidential run. (And within a week, she defended the proposal in front of ample tech sector employees at SXSW 2019. "My view is break those things apart, and we'll have a more robust market in America.")

- May 9: Facebook co-founder Chris Hughes pens a lengthy op-ed in the New York Times making the case for breaking up Facebook sooner rather than later.

- June 3: The House Antitrust Subcommittee announces a bipartisan investigation into competition and "abusive conduct" in the tech sector.

- June 3: Reuters, The Wall Street Journal, and other media outlets report that the FTC and DOJ have settled on a divide-and-conquer approach to antitrust probes, with the DOJ set to take on Apple and Google, and the FTC investigating Amazon and Facebook.

- July 24: The Department of Justice publicly confirms it has launched an antitrust probe into "market-leading online platforms." The DOJ does not name names, but the list of potential targets is widely understood to include Apple, Amazon, Facebook, and Google.

- July 25: Facebook confirms it is under investigation by the FTC.

- September 6: A coalition of attorneys general for nine states and territories announce a joint antitrust probe into Facebook.

- September 6: Google publicly confirms it is the target of a DOJ antitrust probe.

- September 9: A coalition of attorneys general for 50 states and territories announce a joint antitrust probe into Google.

- September 13: House Antitrust Subcommittee sends an absolutely massive request for information to Apple, Amazon, Facebook, and Google, requesting 10 years' worth of detailed records relating to competition, acquisitions, and other matters relevant to the investigation.

- September 25: Media reports indicate the DOJ is also probing Facebook.

- October 22: An additional 38 attorneys general sign on to the states' probe of Facebook, bringing the total to 47.

Although all four of Apple, Amazon, Facebook, and Google are US companies, they operate worldwide, and scrutiny of them is by no means limited to US regulators. Governments and regulatory agencies worldwide, especially in the European Union and its member states, also have several open investigations of all four companies in progress.

Listing image by Justin Sullivan/Getty Images

What kind of stuff can they actually investigate?

Bigness by itself is not a crime, and none of the four platforms currently known to be under investigation is necessarily a monopoly in the sense the Sherman Act would have it. You can use a status- and photo-sharing platform that isn't Facebook, you can shop from retailers other than Amazon, and you can buy a phone made by neither Apple nor Google. The companies also compete with each other in many ways: Apple and Google compete in phone hardware and software, and Google, Facebook, and Amazon compete in digital advertising, for example.

There's no denying, however, that these four companies are dominant, and there are a couple of broad avenues of investigation available to everyone who's digging in.

One has to do with monopoly power and theories of consumer harm. Generally, if a company is a monopoly or a near-monopoly, then consumers can expect to see prices increase more or less unchecked, for example. Or perhaps, with no competitor spurring one along, the quality of service severely degrades.

Shoppers do pay for products on Amazon and from Apple, but for Facebook and Google the picture is murkier. Individuals don't hand over any cash to use those services. Rather, the business model of Facebook and Google is to harvest information from individuals that is then remixed and endlessly sold.

DOJ antitrust chief Makan Delrahim has made the case that something like worsening privacy standards, however, may still count as diminished service. "Price effects alone do not provide a complete picture of market dynamics," Delrahim said in June. "Diminished quality is also a type of harm to competition. As an example, privacy can be an important dimension of quality. By protecting competition, we can have an impact on privacy and data protection.

"Two companies can compete to expand privacy protections for products or services, or for greater openness and free speech on platforms," he added. "Where competition pushes companies to develop quality elements that better satisfy consumer preferences, our enforcement can protect that sort of competition, too."

That entire line of inquiry is the subject of a great deal of debate among economists, privacy experts, antitrust experts, and basically everyone with an opinion on Facebook's existence. The existing theories of harm used under current antitrust law to codify the kind of damage a company that deals in data and that has literally billions of users may be inflicting on those users, or on other companies, requires abstract arguments and abstract thinking.

Competition regulators in Germany in February became the first to use antitrust regulations to impose privacy controls. The Bundeskartellamt issued a ruling imposing "far-reaching restrictions" in the way the company uses data, calling it an abuse of market power. Among those restrictions is a requirement that Facebook only integrate data from disparate sources, such as WhatsApp, Instagram, the core app, and other Web activities, if users opt-in.

Facebook appealed the ruling. A German regional court granted an injunction to Facebook in late August; the regulator said it planned to file an appeal of the lower court's ruling with the Federal Court of Justice, Germany's highest court.

Breakdown: Competition

Much more tangible, however, is the other avenue of antitrust inquiry: how did these companies rise to the top, and how do they stay there? Is everything above board, or have any dirty, underhanded, unlawful cards been played? All of the companies currently under investigation have faced repeated accusations in recent years of leveraging their size and vertical market power to shove out competitors in comparatively old-fashioned unfair ways. Some examples:

Apple

Apple launched the first iPod in 2001, transforming itself from a computer company to a company that understood that the future of computers was in your pocket. Jump to 18 years later, and the company is boasting well over a billion active iOS devices running worldwide. Those devices are a combination of Apple hardware and Apple software, and regulators are reportedly probing how Apple leverages its position in the supply chain over others on both ends.

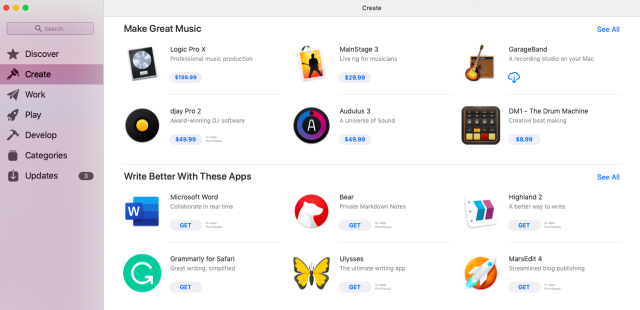

One major avenue of investigation? The App Store, through which every single program that wants to reach users on any of those billions of devices must pass.

Apple has a history of using App Store sales data as something of a free focus group for its own development team. The Washington Post recently explained how Apple uses App Store sales and download data to see which third-party apps gain the most popularity with iPhone users. Apple can then develop a similar app or feature set in-house and distribute it as part of iOS, or the company can promote it more heavily as a native Apple program.

As a result, the WaPo writes, "Some apps have simply buckled under the pressure, in some cases shutting down. They generally don’t sue Apple because of the difficulty and expense in fighting the tech giant—and the consequences they might face from being dependent on the platform."

iPhone users can still choose to install third-party apps, of course, but they cannot set them as default options in lieu of any built-in iOS function, a limitation that is growing more cumbersome for developers as Apple's in-house collection of apps grows.

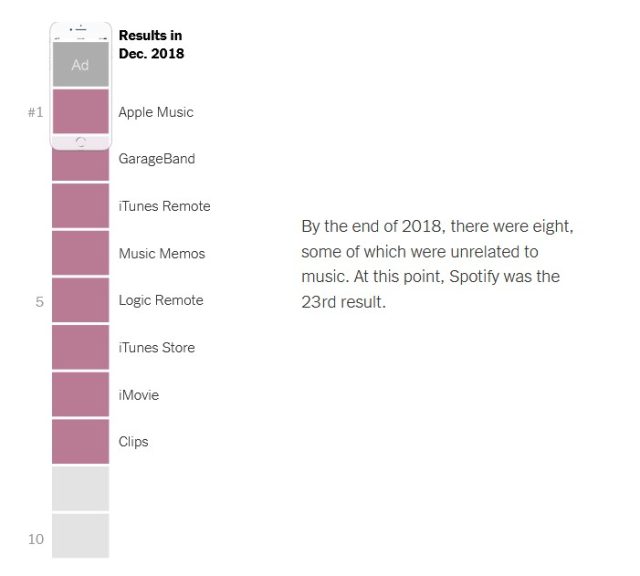

The New York Times also recently published a feature and accompanying graphic showing just how challenging it can be for third-party apps even to be seen in the App Store. First-party programs show up first in the App Store for at least 700 different search results, the NYT reports, with some searches returning as many as 14 separate Apple apps, some unrelated to the search at hand, before displaying results from competitors.

Spotify provides an example. The company, which is based in Sweden, filed a formal antitrust complaint with EU regulators against Apple in March. Spotify used to charge the same €9.99 per month. But in 2014, the company said, it finally switched to using Apple's In-App purchase service. That service means 30% of any revenue Spotify takes in goes directly to Apple.

Spotify raised its prices to €12.99 per month to cover Apple's fees. Apple then launched its own competing service, Apple Music. Apple Music charges subscribers $9.99 (or €9.99, in Europe) per month, and that service does not have the same challenge Spotify and others do of having to allow for 30% of all revenue to go back to Apple.

Spotify also suddenly had a harder time showing up in search results once Apple Music came on the scene, that New York Times report found. In September 2013, Spotify was the first result returned by searches for "music." By June 2016, Apple Music was the first result, and Spotify was down to fourth place—arguably, something that could have happened naturally. By February 2018, though, Apple first-party apps were suddenly the first six results for "music," with Spotify coming in at number eight. And by December 2018, Apple native apps came back as the first eight results in the same search, even though some were completely unrelated to music—and Spotify, one of the world's most popular music streaming services, was all the way down to 23.

By April 2019, one month after Spotify filed its formal complaint with the EU, only two Apple results—the iTunes Store and Apple Music—showed up at the top of the same search results, the NYT reports, with Spotify appearing as result number four.

The complaints against Facebook are legion, spanning basically every aspect of consumer privacy, advertising, and data-gathering you can think of. Several of the US antitrust probes, however, are focusing on something much easier to pin down under existing law: the company's behavior toward would-be rivals.

Facebook has used all available data to guide its own development and acquisition plans in the past 15 years—and every time it completes one of those acquisitions, it gains access to an even larger trove of data it can use to target competitors. Critics allege that all of the big tech firms make it extremely difficult for new businesses to grow and flourish long enough to become true competition, and Facebook is something of a poster child for this problem.

Back in 2013, Facebook spent about $200 million—not very much at all, by its standards—to acquire a startup called Onavo. The companies at the time described Onavo as a provider of mobile utilities and "the first mobile market intelligence service based on real engagement data."

Among the apps Onavo distributed was a VPN called Onavo Protect. The VPN billed itself to users as a way to keep data private by encrypting it—basically, what a VPN is for. However, The Wall Street Journal reported in 2017 that when users opened an app or website, Onavo was redirecting the traffic through Facebook servers, which logged the data.

That data directly informed Facebook's largest-ever acquisition, the WSJ reported: its $19 billion purchase of messaging platform WhatsApp in 2014. "Onavo showed [WhatsApp] was installed on 99% of all Android phones in Spain—showing WhatsApp was changing how an entire country communicated," sources told the WSJ. Facebook confirmed to Congress in 2018 that it used the aggregated data gathered and logged by Onavo to analyze consumers' use of other apps.

(Apple found Onavo to be in violation of its App Store policies and pulled it in 2018; Google Play followed suit a few months later. Facebook finally discontinued the service in May.)

Facebook could use data it harvested from Onavo and other sources not only to target other companies for acquisition but also to identify rival services to clone or suppress. The Wall Street Journal recently reported that Snapchat has a dossier, called "Project Voldemort," outlining how Facebook did exactly that.

Facebook tried twice to acquire Snapchat. It first offered $3 billion in 2013; three years later, in 2016, Facebook again made overtures that Snap turned down in favor of continuing with its early-2017 IPO. After the snubs, Facebook started cloning Snapchat's most popular features: Instagram Stories launched in August 2016, and Facebook Stories followed suit in March 2017.

In addition to copying Snapchat's winning formula on its own platforms, Facebook reportedly basically punished high-profile users who so much as mentioned the competition. Instagram influencers with verified accounts were reportedly warned that mentioning Snap could cost them their coveted blue check mark. Snap executives also suspected Facebook was suppressing content that originated on Snap from trending on Instagram, by blocking the word "snapchat" and certain related hashtags from trending or from appearing in search results.

Facebook's list of acquisitions, and what it does with data and tools it reaps from those companies, is widely reported to be at the heart of the FTC's investigation. Congress is also clearly zeroing in on the company's acquisition strategy as part of its inquiry (PDF).

None of this has caused Facebook to slow down its buying spree: the company said September 25 it had purchased CTRL-Labs, which makes hardware that can interpret signals sent by your body and translate them into virtual motion, for somewhere between $500 million and $1 billion.

!["I'm not just the president [read: marketplace], I'm also a client [read: retailer]."](https://cdn.arstechnica.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/Screen-Shot-2019-11-01-at-1.08.09-PM-640x520.png)

Amazon

Amazon has fingers in, well, just about everything. It's an organic grocery store. It's a bookseller. It's a streaming TV service. It's a streaming music service. It's a purveyor of smart-home goods, including surveillance doorbells beloved of police. It's running a massive percentage of the cloud that makes the modern internet work. It's making inroads into the massive digital advertising market.

A huge number of Amazon's businesses could be the targets of a probe. The clues we have so far, however, indicate that investigators are zeroing in on two main lines of inquiry: Amazon's acquisition history and strategy, and the company's fraught relationship with vendors on its massive third-party marketplace.

Third-party marketplace sales accounted for 58% of Amazon's retail activity in 2018, company CEO Jeff Bezos told investors earlier this year, adding that those third-party vendors sold $160 billion worth of goods. Amazon as a whole, meanwhile, is projected to capture somewhere between 37% and 47% of all US online shopping in 2019, after capturing a little less than half of the market in 2018. With that large a presence in the marketplace, its tactics not only affect consumers but also rivals.

Bloomberg reported in September that investigators from the FTC have been interviewing merchants who sell their wares on Amazon, three of whom spoke to Bloomberg about the experience. "All three merchants fielded questions on how much of their revenue comes from Amazon compared with other online platforms," Bloomberg wrote. "Many sellers get 90% or more of their sales from Amazon, making them vulnerable to the company’s demands and abrupt, unexplained changes in its policy."

The price pressure Amazon puts on marketplace vendors can also affect prices you see from competitors such as Walmart. As Bloomberg explained in a separate story from August:

Amazon constantly scans rivals’ prices to see if they’re lower. When it discovers a product is cheaper on, say, Walmart.com, Amazon alerts the company selling the item and then makes the product harder to find and buy on its own marketplace—effectively penalizing the merchant. In many cases, the merchant opts to raise the price on the rival site rather than risk losing sales on Amazon.

Merchants also spoke to The Washington Post recently about life as an Amazon vendor. The Post wrote:

Early on, Amazon compelled sellers to use its warehouses to guarantee speedy Prime shipping, in addition to other programs that largely benefited consumers. But now, sellers and former employees familiar with Amazon’s internal strategy say the company is increasingly focused on boosting its profits on the backs of its sellers — often without any clear upside for customers.

The services include charging sellers thousands of dollars to speak to account managers, as well as making it necessary to purchase ads to guarantee the top spot on a search page. Plus, Amazon is aggressively pushing its own brands — something that may be cheaper for consumers in the short run, but demonstrates its overall power over pricing and merchandise on the site. That gives it an advantage over rival products and sellers who rely on Amazon for their livelihood and have few alternatives if they want to thrive selling online.

Perhaps even more pressingly, Amazon's dual position as both retailer and platform gives it an edge when it comes to data. That's the issue at the heart of an investigation the European Union's competition bureau is running into the company's marketplace practices, and it seems to be on US regulators' radar as well.

Amazon now boasts more than 80 in-house brands, mostly of apparel and home goods, and it's often far from clear to consumers browsing for something like a shirt which products are actually made by Amazon itself. Critics accuse Amazon of using sales data it gleans from third-party merchants to determine what product lines it should launch, which of its own goods it should most heavily promote, and where and how it should do those promotions.

The company has experimented with different methods of advertising its own house brands on competitors' listings for similar goods. CNBC reported on one method the company was using last year, and The Washington Post in August delved into an even more aggressive tactic Amazon apparently started using this year. More recently, The Wall Street Journal did a deep dive into the way Amazon's sorting algorithm presents search results to consumers.

Sources told the WSJ that Amazon "optimized the secret algorithm that ranks listings so that instead of showing customers mainly the most-relevant and best-selling listings when they search—as it had for more than a decade—the site also gives a boost to items that are more profitable for the company."

Amazon told Ars in September that sales of its house-brand products represent about 1% of its total overall sales. That figure does indicate that any efforts Amazon may have potentially undertaken to stack the deck in its favor to date have not necessarily brought success—but it also indicates a reason the company may be motivated to push its own brands at the expense of others.

Google—or rather, since 2015, its parent company Alphabet—likewise has its hands in a thousand different things. We're a far cry from the era when it was just the Internet's shiniest new search engine, although it is still indeed the dominant force in search. The company manufactures phones and home devices, develops the world's most-used mobile operating system, operates the world's dominant video-sharing platform, and has the most dominant Web browser in the world, among other things. The company has been the target of at least a half-dozen previous US and EU antitrust probes, and it has cumulatively paid billions in penalties and settlements over the past decade or so.

But of all Google's many ventures, the biggest by far is its advertising business. Advertising accounted for $32.6 billion of Google's total $38.9 billion of revenue in the second quarter of this year, or a little under 84%. Digital advertising spending in the US is forecast to surpass spending on traditional forms of advertising (print and television, mostly) in 2019, and Google is the largest player in that market by far.

Analytics firm eMarketer has forecast that Google will likely command more than 20% of all US ad spending, not just digital advertising spending, in 2019. Overall, it is forecast to capture about 37% of the digital ad market—down from its halcyon days, to be sure, but still well ahead of second-place rival Facebook, which is forecast to capture about a 22% share.

That advertising business is the initial focus of the antitrust probe into Google's businesses that 50 attorneys general have banded together to launch. Bloomberg in September obtained a copy of the 29-page civil investigative demand Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton's office sent to the firm.

The opacity of the advertising and data markets not only make it harder for consumers to understand how their data is being gathered and used, but they also make it more difficult for regulators to tease out which threads in the dense web might be anticompetitive. The request is, first and foremost, a request for information about how the marketplace even works, Bloomberg reported:

The states want information about Google’s past acquisitions of advertising technology companies, including DoubleClick and AdMob; its top advertisers and publishers; data collection practices; pricing models; and the functions of the ad auction market that delivers ads across the internet.

The document’s questions dig deep into the “black box” of Google’s money-making machine and ask for a thorough explanation of how it all works. Even to experts, the ad tech market can seem opaque and dizzying in its complexity.

The process of showing an ad to a single person visiting a web page can involve dozens of companies and multiple auctions and transactions. Google has worked its way into controlling much of that process, and investigators want to know exactly how powerful the company has become in this space.

Reports indicate that Google's advertising and search practices are the key operations at the heart of the DOJ's federal antitrust probe of Google as well, since the company's sprawling reach gives it access to almost every link in the complicated ad sales chain.

Google in a company blog post countered that the digital advertising technology industry is "crowded and competitive," adding, "The industry is famously crowded. There are thousands of companies, large and small, working together and in competition with each other to power digital advertising across the web, each with different specialties and technologies."

Though the antitrust probe into Google is beginning with advertising, it doesn't seem it will end there. "If we end up learning things that lead us in other directions, we’ll certainly bring those back to the states and talk about whether we expand into other areas," Paxton told the Washington Post in an interview.

But will anything actually change?

Regardless of whether it should be, all regulation in the current era is highly political. Even something as theoretically anodyne and broadly popular as net neutrality is a partisan football these days, endlessly kicked, carried, and thrown back and forth. Big tech regulation is no less contentious. Politicians on both sides of the aisle have proposed reining in the tech titans, but their reasons why, and what specific form any new laws or regulatory enforcement might take, is much harder to find consensus on.

Until then, the most likely outcome from an antitrust probe—or even, apparently, an overflowing cornucopia of antitrust probes—is a combination of financial penalties and behavioral remedies. A company might, for example, be ordered to stop using data it collects from one aspect of its business to influence decisions it makes about competitors through another aspect of its business. A breakup is considered something of a nuclear option.

And even if Facebook, Amazon, Apple, or Google were somehow forced to split up tomorrow\, big tech breakups might only be a short-term fix. Like beads of mercury in a dish, companies broken apart by antitrust law have a strange way of eventually all flowing back together.

By the time we were 30 years out from the Bell breakup, for instance, none of the regional Baby Bell carriers existed as corporate entities any longer. A tangled web of mergers and acquisitions led all of them back to one of three places. CenturyLink inherited one, Verizon rose from another two, and all the rest ended up right back where they began: as parts of AT&T.

And though the landline telephone business that made AT&T into a national monopoly has spent the current century in a state of decline, AT&T still arguably remains the nation's largest phone company. In any given quarter, it boasts either slightly more or fractionally fewer wireless customers than rival Verizon, each claiming between 150 million and 160 million subscribers. AT&T hasn't stopped with "just" phone coverage, either. In 2015, the company became the nation's largest pay-TV provider when it acquired DirecTV for $48.5 billion (although that acquisition has not been going well lately). It then followed the footsteps of fellow pay-TV provider Comcast into the content game, spending $85 billion to acquire Time Warner in 2018.

So to imagine just one future from these four Big Tech antitrust initiatives, take Facebook. WhatsApp and Instagram each boast more than a billion users. If Facebook were somehow forced to divest both companies tomorrow, the businesses might stand alone for a time. Or, more likely, they might go to other deep-pocketed buyers—buyers that, themselves, would then be subject to the tug and spin of shareholders and economic forces, and the platforms might eventually start gravitating toward each other all over again until they inevitably collide.

https://arstechnica.com/tech-policy/2019/11/antitrust-101-why-everyone-is-probing-amazon-apple-facebook-and-google/

2019-11-05 12:00:00Z

CBMic2h0dHBzOi8vYXJzdGVjaG5pY2EuY29tL3RlY2gtcG9saWN5LzIwMTkvMTEvYW50aXRydXN0LTEwMS13aHktZXZlcnlvbmUtaXMtcHJvYmluZy1hbWF6b24tYXBwbGUtZmFjZWJvb2stYW5kLWdvb2dsZS_SAXlodHRwczovL2Fyc3RlY2huaWNhLmNvbS90ZWNoLXBvbGljeS8yMDE5LzExL2FudGl0cnVzdC0xMDEtd2h5LWV2ZXJ5b25lLWlzLXByb2JpbmctYW1hem9uLWFwcGxlLWZhY2Vib29rLWFuZC1nb29nbGUvP2FtcD0x

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19308787/header_command_line_option_32x.png)